Building a Realistic Boat-Water Interaction System from Scratch

Try playing the simulation on Itch!

Introduction: Why Take on This Challenge?

When I embarked on this project, I wasn't just looking for another programming exercise. I wanted to push myself into unfamiliar territory - implementing a physics simulation system with minimal reliance on existing tools. The idea of working at a low level, manipulating mesh polygons directly, solving complex mathematical and physics problems in code, and tackling performance optimization challenges was both intimidating and exciting. There was something magical about the prospect of creating realistic water physics from fundamental principles.

This project would take me through ocean rendering, boat physics simulation, and the intricate dance between performance and accuracy that defines real-time systems.

Part 1: Creating the Ocean

Starting with Rendering

My initial goal was straightforward: simulate realistic boat physics. Ocean rendering was actually secondary - I was prepared to fall back on open-source solutions or Unreal's water plugin if necessary. However, I discovered a practical and elegant way to render ocean surfaces using Gerstner wave equations, and decided to implement it myself.

Understanding Gerstner Waves

The foundation of ocean simulation lies in Gerstner waves, which create realistic water surface deformation. The basic concept is surprisingly simple: each wave follows a sinusoidal equation, and you can layer as many sine waves as needed for complexity. The challenge comes in summing up these sine waves for each vertex on the mesh in real-time.

The basic vertical displacement is just the beginning. To create truly realistic water movement, I needed to modify the X and Y coordinates as well, making the water appear to flow and undulate naturally. The complete Gerstner wave equation handles this three-dimensional movement, creating the characteristic circular motion of water particles that sailors observe in real ocean waves.

The Lighting Challenge

One of the trickier aspects of dynamic ocean rendering is lighting. Unreal Engine needs normal vectors from a mesh to properly apply lighting calculations. When vertices are manipulated every frame, calculating the normal vector at each vertex becomes computationally expensive.

The solution involves computing normals using the cross product of binormal and tangent vectors. This mathematical approach ensures that the lighting responds correctly to the constantly changing ocean surface, creating realistic highlights and shadows that sell the illusion of water.

Part 2: Implementing Physics Interaction

Foundation Questions

Before implementing any physics, I needed to solve several fundamental problems. How would I determine the intersection between the water surface and the boat's hull? How could I apply forces to the boat realistically? Could I access and manipulate the individual triangles of the boat's mesh?

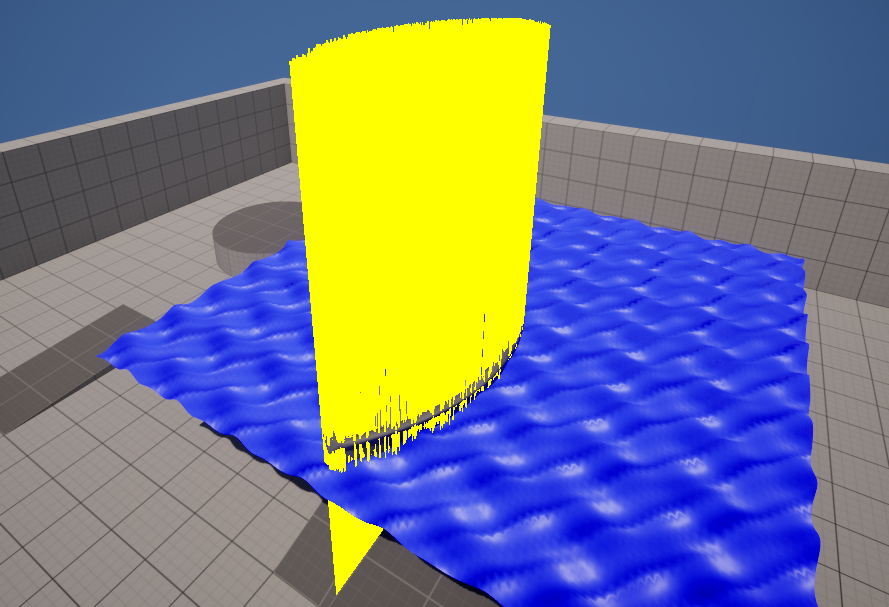

These questions led to deeper technical challenges. How could I verify that my list of triangles was accurate and properly positioned? More critically, how would I determine which triangles were submerged at any given moment, and what about partially submerged triangles?

Synchronization and Debugging

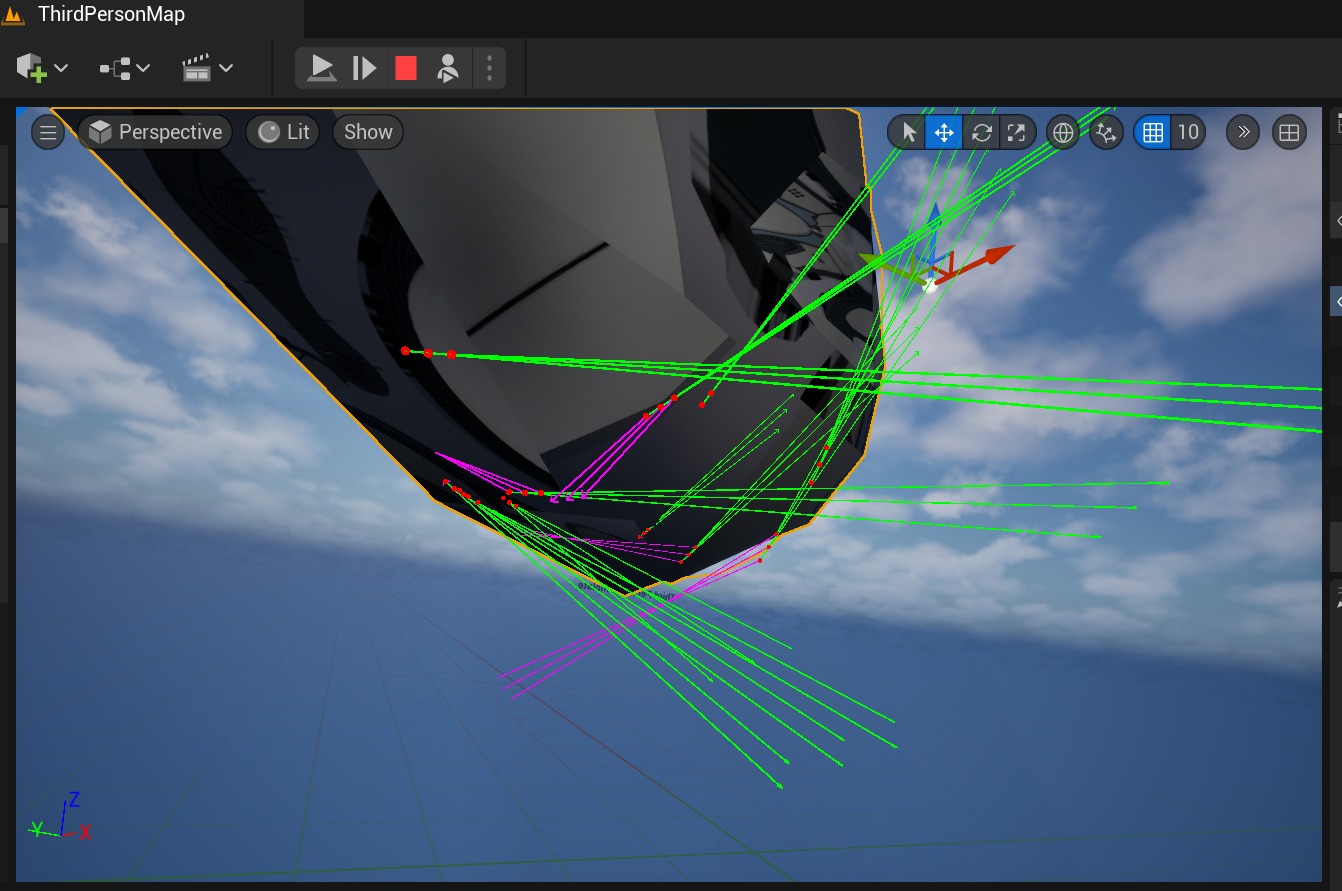

One of the first major hurdles was ensuring that the positional data of the ocean mesh and boat mesh were perfectly synchronized. To debug this, I created visual debugging tools - debug lines that showed the projection of the boat onto the ocean surface. This visual feedback proved invaluable throughout development.

Early in the process, I made a crucial decision: working with a real boat mesh containing over 1,000 vertices made debugging nearly impossible. Instead, I switched to using a simple cube as a proxy boat. This simplification allowed me to verify my algorithms were working correctly before scaling up to more complex geometries.

The Cutting Algorithm

The heart of the physics system is determining which parts of the boat are underwater. This required developing a cutting algorithm to identify submerged triangles. I explored several approaches:

First, I attempted using raycasts from the boat's triangles onto the ocean mesh. While conceptually simple, this proved inefficient and occasionally unreliable. Next, I tried an analytical approach, sampling the ocean mesh height at given x,y,t coordinates. Ultimately, I found that using the wave equations directly to sample height at any position and time was both the fastest and most accurate solution.

For partially submerged triangles, I interpolated between submerged and non-submerged vertices. This process would result in either smaller triangles or quadrilaterals, which could then be processed for physics calculations.

Early Physics Disasters

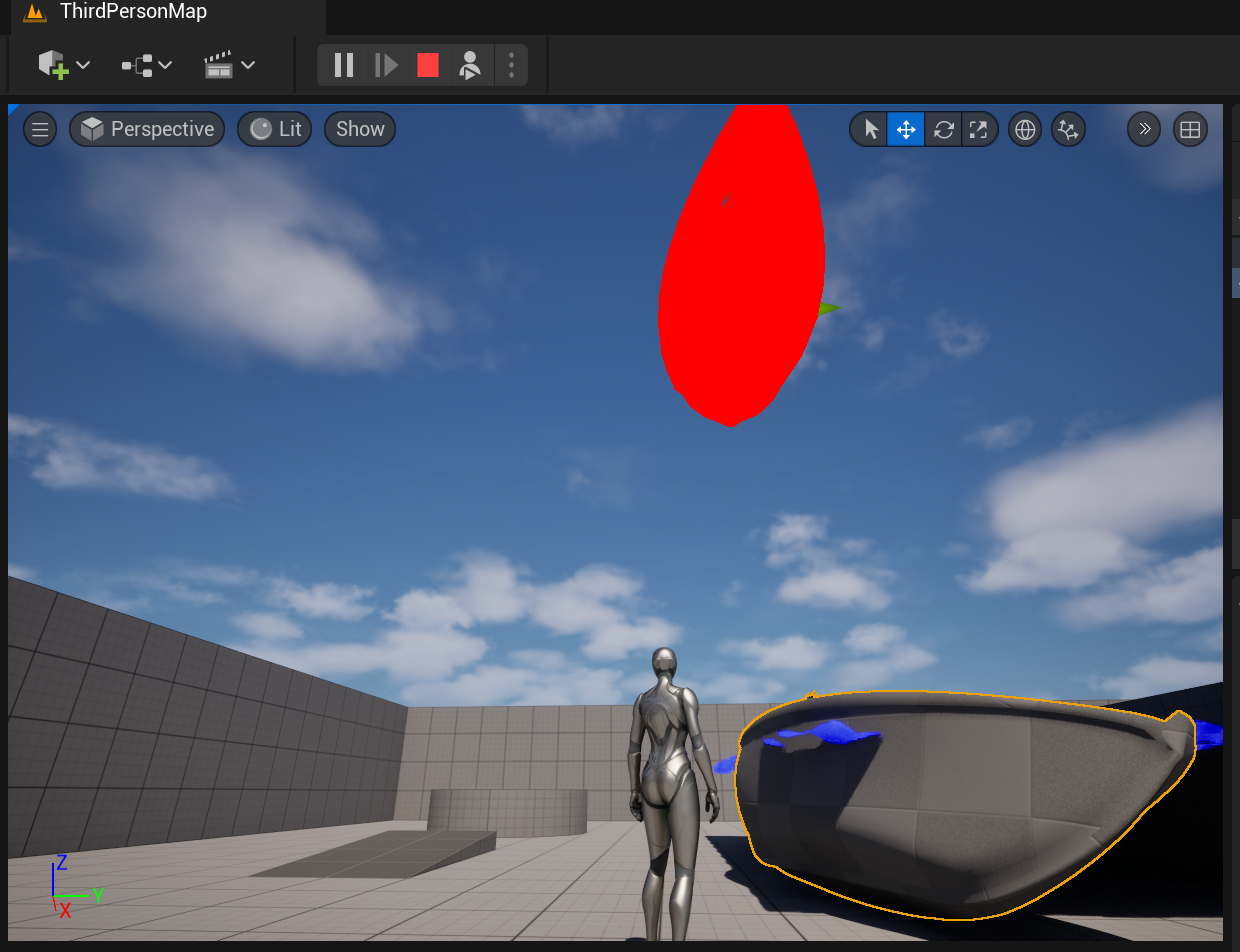

My first attempts at implementing buoyancy led to spectacular failures - boats launching into the stratosphere instead of floating peacefully. These dramatic results taught me several critical lessons:

The improper calculation of area, mass, and force was being amplified by the velocity of falling objects. I discovered that Unreal Engine expects all distances in centimeters and forces in centi-Newtons - a detail I had initially overlooked. This unit mismatch was causing forces to be off by orders of magnitude.

Additionally, physics in game engines operates in discrete time steps, unlike the continuous physics of the real world. This meant falling objects would penetrate the water surface more than they should, resulting in massive overcorrection from the buoyancy forces.

Performance and Stability Issues

Early implementations suffered from poor frame rates, noticeable lag, and system instability. I observed that forces seemed to apply to the boat with a delay after water contact. Through careful debugging, I discovered that the total buoyant force was approximately 10 times greater than the object's weight. In reality, at equilibrium, buoyant force should exactly cancel out gravitational force.

Part 3: Refining the Simulation

Adding Viscosity and Drag

Buoyancy alone created unrealistic motion - boats would bounce on the water surface like trampolines. Implementing drag forces was essential for realistic behavior. Viscosity is a complex force with many variables and is harder to observe and tune than buoyancy. Even among scientists and marine experts, water resistance isn't completely understood, relying heavily on empirical formulas from experimental data.

Factors influencing viscosity include surface area, boat speed, turbulence, surface roughness, and boat shape. The Reynolds number (Rn) - a dimensionless value indicating whether flow is turbulent or laminar - became a key parameter in my calculations. The relative velocity of water flow tangential to surfaces (Vfi) also played a crucial role.

Pressure Drag and Empirical Forces

Beyond basic viscosity, I implemented pressure drag forces. These don't correspond to specific physical phenomena but rather account for the total resistance exceeding viscous resistance alone. This includes wave pattern resistance, spray resistance, and eddy forces - all derived from empirical formulas developed through decades of marine engineering research.

Part 4: Critical Optimizations

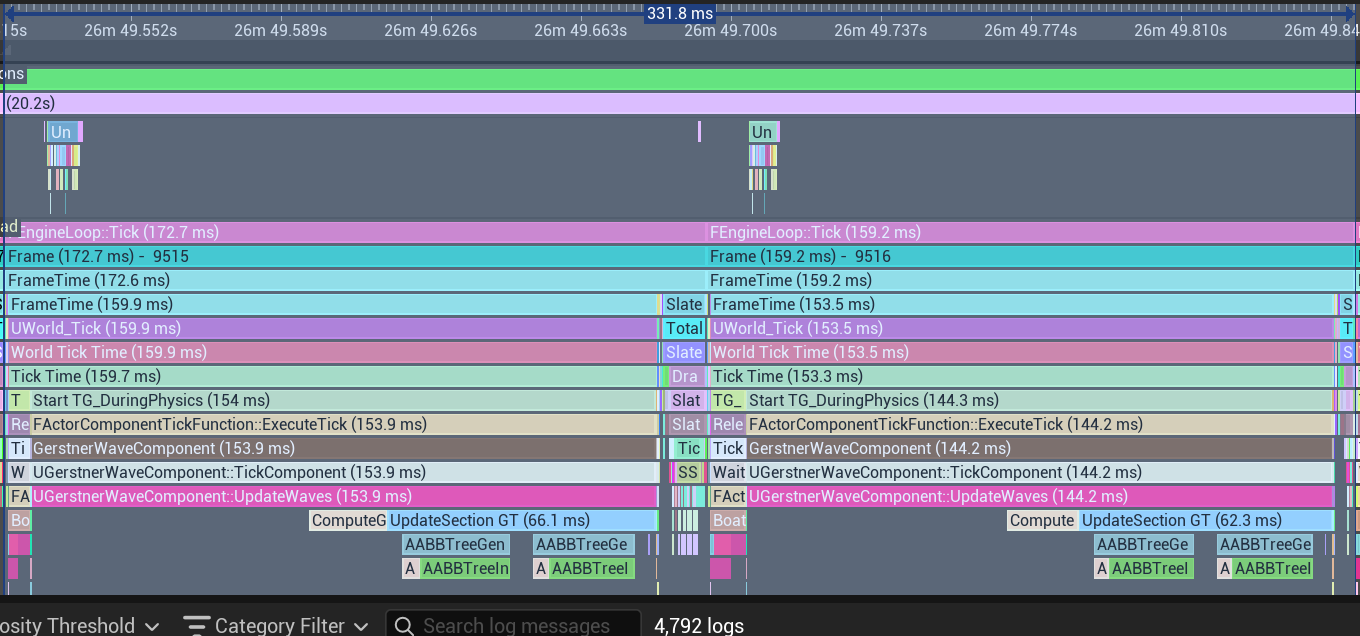

Identifying Performance Bottlenecks

The system faced two major performance problems. Ocean rendering was extremely expensive - rendering a procedural mesh of 1000x1000 vertices was choking the CPU. Additionally, force computations were consuming significant processing time.

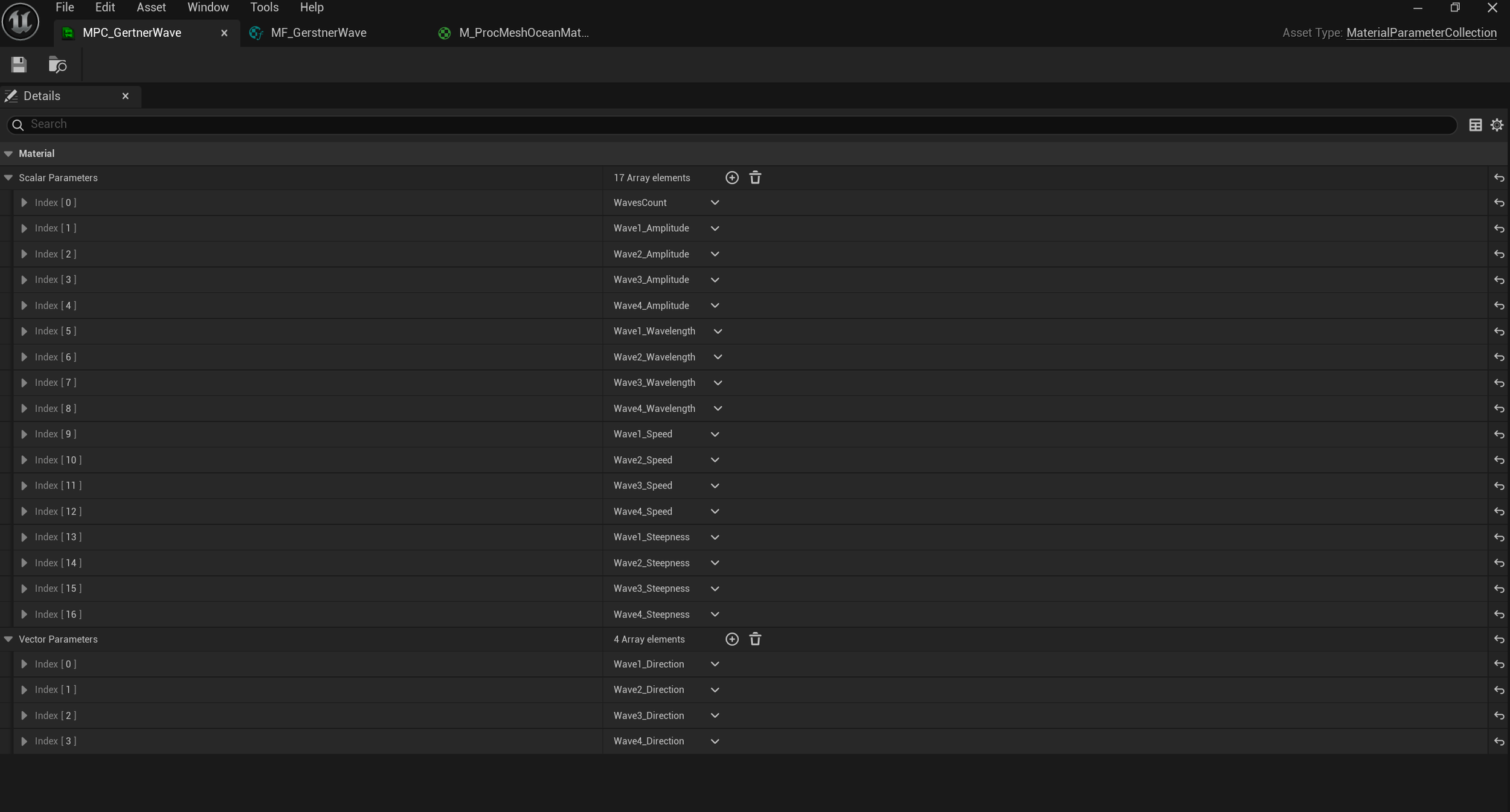

GPU-Based Ocean Rendering

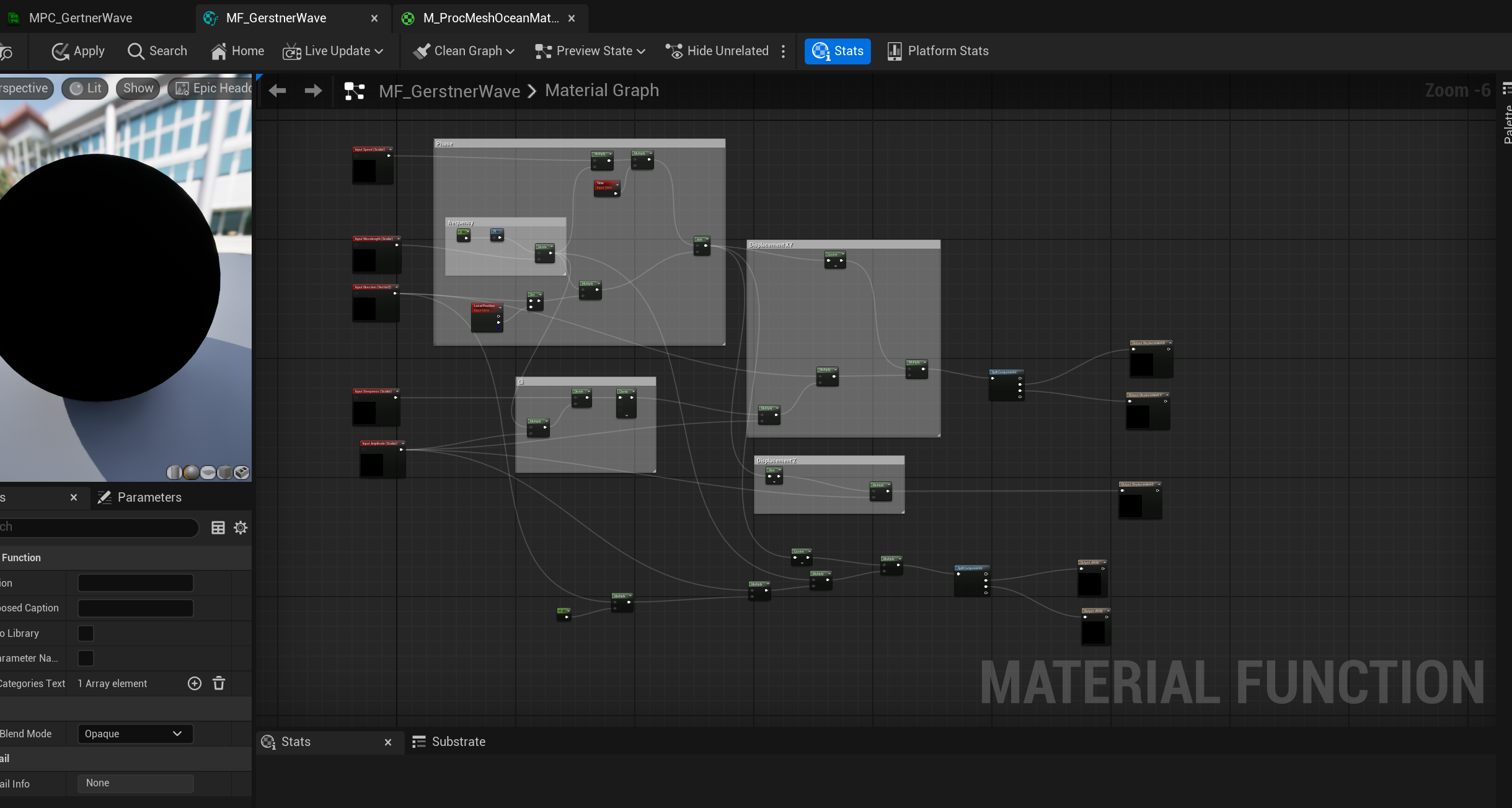

The solution for ocean rendering was moving calculations to the GPU. I learned to use Unreal's material editor, writing a material function to compute waves on the graphics card. To keep wave properties synchronized between the material and CPU code, I implemented a data table system storing all wave parameters, fetched by the code at startup. This GPU migration provided dramatic performance improvements.

Multithreading Force Computations

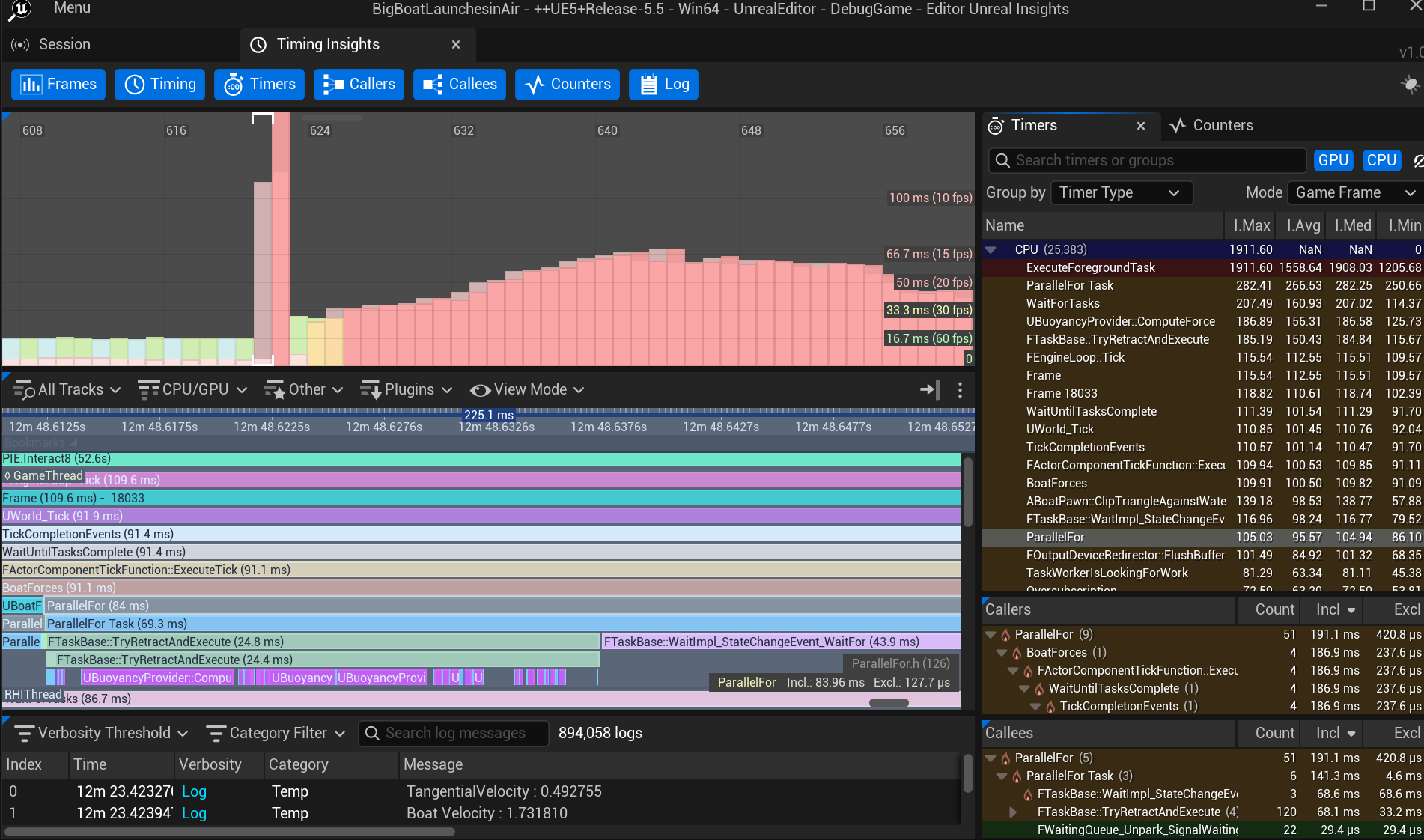

I refactored the force computation code from single-threaded to multi-threaded using Unreal's TaskGraph system, which maintains a pool of worker threads and schedules submitted tasks efficiently.

The challenge with multithreading was finding the right granularity. Creating a task for every polygon would introduce excessive overhead from context switching. My solution was to create batches of polygons and assign one task per batch, finding the sweet spot between parallelization and overhead.

Performance profiling revealed interesting patterns - computation spikes occurred as the boat moved deeper into water, processing more submerged polygons. This variable workload made consistent frame rates challenging to maintain.

Part 5: Architecture and Refactoring

Layered Architecture

I undertook two major refactoring exercises to improve code organization and maintainability. The second refactoring organized the plugin code into managed and native layers. While the native layer ideally should have no Unreal dependencies, I settled on a semi-native approach depending only on Unreal's Core module.

This architecture kept all Unreal-specific classes and logic in the managed layer while isolating computational features and physics logic in the native layer. This separation made the code more testable, portable, and maintainable.

Key Learnings and Best Practices

Through this project, I learned several valuable lessons about real-time simulation development:

Problem Decomposition: Complex problems can be overwhelming. Just as I simplified the 1000+ vertex boat to a simple cube for debugging, breaking down problems into manageable pieces is crucial for understanding and solving them.

Visual Debugging in Real-Time Systems: Traditional debugging with breakpoints and watch windows is often impractical in real-time systems. Visual debugging tools like real-time logging and debug draws proved invaluable for understanding dynamic behavior that would be impossible to catch with conventional debugging techniques.

Premature Optimization: Resist the temptation to optimize early. As the system develops, you'll often discover that performance bottlenecks come from unexpected sources. Profile first, optimize second.

Incremental Development: When implementing complex features like buoyancy and viscosity, I isolated and tested each component in controlled environments before integration. This methodical approach built confidence in each subsystem.

Refactoring Strategy: During refactoring, I initially tried to change too much simultaneously, making the codebase unmanageable. Success came from making specific, low-impact changes, integrating them back to the main codebase, and repeating the process iteratively.

Conclusion

Building a boat-water interaction system from scratch was a journey through physics, mathematics, computer graphics, and software engineering. It challenged me to think about problems from multiple angles - from the theoretical physics of fluid dynamics to the practical concerns of real-time performance.

The project succeeded not just in creating a working simulation, but in deepening my understanding of how complex natural phenomena can be approximated in real-time systems. Each challenge overcome - from unit conversion errors launching boats skyward to architecting a maintainable codebase - added to my toolkit for tackling complex technical problems.

Most importantly, this project reinforced that the most intimidating technical challenges become manageable when approached systematically, with good debugging tools, and a willingness to iterate and refine. What began as "magical and full of wonder" became understood, implemented, and optimized - though no less wonderful for being understood.